|

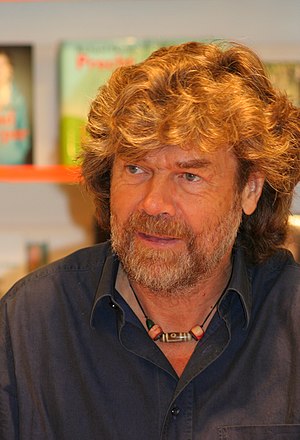

| Mountaineer and author Reinhold Messner authographs in Cologne, Germany. Русский: Альпинист и автор Райнхольд Месснер раздаёт автографы в Кёльне (Германия). (Photo credit: Wikipedia) |

Beyond the walls of the 16th-century fortress, in northern Italy, the Dolomite range rose burnished and glowing in the late afternoon light. Within the walls, Reinhold Messner, the world's greatest mountaineer, was building a mountain. At his energetic direction, a backhoe lumbered back and forth in the dusty courtyard, heaving slabs of rock and depositing them in an artful pyramid that by the end of the exercise had formed a small mountain.

"This is Kailas, Holy Mountain," Reinhold said, while the backhoe ?lled the air with golden dust. He was relishing the scene - the whole scene; not just the satisfaction of seeing Tibet's most holy mountain assembled in miniature under his supervision but also, I suspected, the roar and rumble and chaos and dust and magni?cent improbability of the undertaking. The Kailas installation is only one of the many features, fanciful and inspired, that will ?ll his latest Messner Mountain Museum, this one dedicated to the theme of "When Men Meet Mountains."

Reinhold Messner is well into what he has designated Stage Six of his already remarkable life, without, it would seem, a backward glance for Stage One, when he was one of the world's elite rock climbers, or Stage Two, when he was unquestionably the world's greatest high-altitude mountaineer. Today, at 62, he is instantly recognizable from the multitude of publicity photographs taken over the past three decades - lean and ?t and sporting an even longer mane of waving hair, now threaded with silver, than he did when younger. His features tend to alternate between two characteristic expressions: The ?rst, a look of ?erce intensity, which, combined with beetling eyebrows and flowing beard and hair, give him an air of Zeus-like authority. It was with this expression that he moved his mountain. The second is his trademark smile - a reflexive baring of his very white, even teeth behind his beard - which gleams on friend and foe without distinction, like the smile of a crocodile. It was the crocodile smile he was baring now, as he envisioned the climactic moment of opening night of the Messner museum: A violent explosion, simulating a volcanic eruption, was to rend the night from inside the castle walls. "There should be a lot of flames and smoke," he said, again with relish. "It should be at night so that the whole of Bolzano can see." He paused to savor the image of a ?reworks blast that would appear to viewers as a catastrophic blowup. "Then my friends will say, 'It is a pity,' and my enemies will say, 'Good, ?nally, at last!'"

To non-climbers it may be dif?cult to convey the extent and grandeur of Reinhold Messner's accomplishments. Here's a start: His ascent, with longtime partner Peter Habeler, of Hidden Peak, the 26,470-foot (8,068-meter) summit of Gasherbrum I, one of the giants of the Himalaya, without any of the paraphernalia of traditional high-altitude climbing - porters, camps, ?xed ropes, and oxygen - was hailed as forging a whole new standard of mountaineering. But that was back in 1975, before Messner and Habeler went on to climb Mount Everest without oxygen, a feat that took climbing to the absolute limit. That, in turn, was in May of 1978 - three months before Messner climbed Nanga Parbat, the ninth highest mountain on Earth, solo - a feat heralded as one of the most daring in mountaineering. That, however, was two years before he climbed Mount Everest without oxygen, equipped with a single small rucksack - and alone.

"It is very dif?cult to calibrate high-altitude climbing," said Hans Kammerlander, who has climbed seven of the world's fourteen 8,000-meter mountains with Messner. "There is no referee, there is no stopwatch. There were others - Buhl, Herzog, Forrer," he said, running through the names of climbing greats. "They did more solo climbs. But Reinhold had so many new ideas - he found new ways, new techniques. He imagined them, and then he put them into practice. So, all around, yes, he does deserve the title of being the greatest mountaineer in history."

Messner's contribution to his profession is not only a list of astonishing feats but also the unrelenting philosophy that lay behind them. "I'm only interested in our experiences and not in the mountains - I'm not a naturalist," he told me. "I'm interested in what's going on in the human beings. . . . William Blake wrote a line, when men and mountains are meeting, big things are happening," he said, paraphrasing a favorite quote from the 18th-century poet, and the philosophy behind his new museum. "If you have a high-way on Everest, you don't meet the mountain. If everything is prepared, and you have a guide who is responsible for your security, you cannot meet the mountain. Meeting mountains is only possible if you . . . are out there in self-suf?ciency."

In an essay he wrote when he was only 27, he decried the siege tactics that allowed even an unskilled climber to conquer a mountain bolt by bolt, issuing a plea for both the mountain that cannot "defend itself" and for the climber, who was being cheated of the opportunity to test the limits of his courage and skill. Titled "The Murder of the Impossible," the essay, now considered a minor classic, argued that the wielders of expansion bolts and pegs "thoughtlessly killed the ideal of the impossible." Messner's characteristic minimalism - he is adamant he has never put an expansion bolt in a face of rock, as he has never used bottled oxygen - was, therefore, a brash demonstration that the principles he preached could be put to spectacular practice. His landmark high-altitude alpine-style climbs liberated both the individual climber, by showing alternatives to the hugely encumbered and expensive classic expeditions, as well as the mountains themselves. The irony, of course, was that it was Messner who, by these very achievements, murdered and laid in the dust all traditional notions of what constituted "the impossible." {Read on}